VASE lecture series 2025-2026: Yoshua Okón

VASE lecture series 2025-2026: Yoshua Okón

Artist Yoshua Okón gave a lecture at the Center for Creative Photography about his works and the violence in the world that inspired them.

El artista Yoshua Okón dio una conferencia en el Centro de Fotografía Creativa sobre sus obras y la violencia en el mundo que las inspiró.

5.12.2025

Mia Payette for The Daily Wildcat

Mia Payette para The Daily Wildcat

The School of Art annually hosts the VASE lecture series, from visiting artists and scholars, at the Center for Creative Photography. The first lecture in this academic year’s lineup featured Yoshua Okón and took place in the CCP auditorium at 5:30 p.m. on Oct. 16. Many students and viewers filled the auditorium ready to learn and even came prepared with questions.

Okón is an artist from Mexico City who earned his Masters of Fine Arts from UCLA with a Fulbright scholarship. Okón co-founded La Panadería in 1994 with artist Miguel Calderón, an exhibition space for rising Mexican artists who are using unconventional mediums. He currently works with other artists to run SOMA, an investigative art group that looks at what art can be in different contexts.

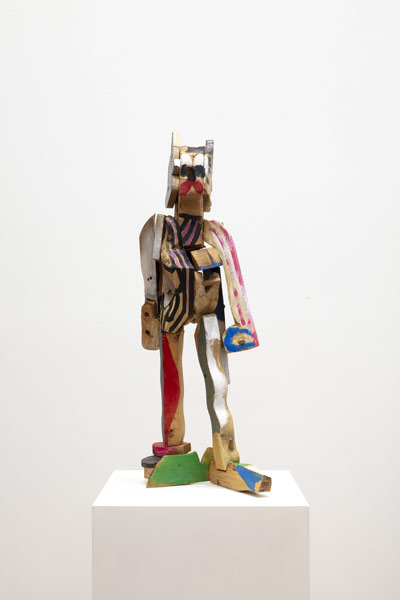

Okón’s works, which include video installations, photography, performances and more, have been exhibited around the world and are in important collections such as the Tate Modern, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Colección Jumex and more. Last year, his collaborative piece “Demo” with ASU professor Juan Obando was exhibited at Tucson’s own Museum of Contemporary Art.

“Broadly framed, his output complicates the boundary between reality and fiction, examining contradictions and absurdities that reveal the mechanics that underlie politics, market systems and neoliberal ideologies. His work critiques systems of power, and interrogates how we understand reality, truth and autonomy,” Associate Dean of Faculty Affairs, professor David Taylor, said about Okón’s work.

“I consider myself generally a happy person and I really enjoy life, but I do also notice a lot of violence around me. I think the neoliberal form of capitalism is a very violent system, that’s why in my work I’m interested in addressing systemic violence beyond official narratives that usually explain it in a simplistic and deceiving way,” Yoshua Okón said.

Okón began the lecture by showcasing one of his early works from the 1990s, “Oríllese a la Orilla,” a series of videos of policemen from Mexico. Each video had no script, no rehearsal and was taken in a single shot. Okón invited the policemen to his studio to engage in a fight, and another to perform with his baton, after he saw him playing with it in the streets. He offered to pay them, and one agreed to be a part of the video as long as he got to insult Okón. “Well, generally speaking, we like to be in front of cameras, we enjoy it. I mean look at today’s world,” Okón responded after being asked about the motivation each policeman had for being a part of the series.

According to Okón, the vertical format barely existed at this time, but he shot them that way for the installation, and how they would be viewed. He had always wondered how to use the video medium in a way that engages participation, opposed to how it had been passively consumed. “It was very important to create this tension between documentary and reality. For the public to ask these questions. ‘How real is this?’ […] ’How fictional is what I’m watching?’ In reality this is both. It’s very artificial of course, and I’m asking them to come into my studio, but at the same time, I’m not in full control, there’s no script,” Okón said about “Oríellese a la Orilla.”

The next piece Okón shared was from 2011, called “Octopus.” This was created almost a decade after he received his MFA, when he was invited by the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles to do a research residency. This piece is inspired by undocumented day laborers who get hired in Home Depot parking lots, and what he read about the Guatemalan civil war. The work contains a group of ex-guerillas reenacting the civil war they fought in, in the Home Depot parking lot.

It consisted of many rehearsals where the actors showed the moves they used in the war, and then created choreography to be performed in the parking lot, which he had no control over.

“The sense that I got was that they were excited to engage in something that was about who they are, their history. Hardly anyone knows that the U.S. invaded Guatemala, and how that connects to them being here now. They were excited to kind of be a part of this […] and the tension of the shoot had more to do with being kicked out of the parking lot than anything else to be honest,” Okón said. “When I made this piece I really wanted to talk about forced migration, in the context of geopolitics, and in the context of the U.S. foreign policy, and mostly in the context of global capitalism and this kind of violence that is invisible to us, and that is pretty much behind forced migration […] I wanted to give that kind of dimension to war, opposed to the glorification of war that never gives the full picture.”

Next, Okón talked about “Oracle,” a piece he made in 2014 in Oracle, Arizona, after getting an invitation from the ASU Art Museum to produce a new work and do an exhibition. This piece was inspired by the news of unaccompanied children coming into the United States from Central America, and the news of a big protest happening in Oracle, about protecting the border. He thought of this piece as a second part of “Octopus,” and the actors reenacted their protest. “There’s kind of an organic aspect to the way these works get created because I usually work with what I find in the world […] and then from there, I build. And in different cases, the degree of fiction can vary depending on the ideas that I come up with and the specifics of the situation,” Okón said. When starting a work, he always approaches people as an artist and explains the context of the art and the exhibit.

Due to time, the night briefly ended with a debut of Okón’s brand new piece that he had just shot and edited. “I’m hoping that through my art, people reflect around the issues that I’m presenting […]. I’m not interested in them reaching any specific conclusion, but I like the reflexive process in itself, the expansion of consciousness and the understanding of the world in more complex and nuanced ways. That’s one of the main reasons why I make art,” Okón said.

La Escuela de Arte organiza anualmente la serie de conferencias VASE, impartida por artistas y académicos visitantes, en el Centro de Fotografía Creativa. La primera conferencia de este año académico, a cargo de Yoshua Okón , tuvo lugar en el auditorio del CCP a las 17:30 h del 16 de octubre . Numerosos estudiantes y espectadores llenaron el auditorio, dispuestos a aprender e incluso llegaron preparados con preguntas.

Okón es un artista de la Ciudad de México que obtuvo su Maestría en Bellas Artes en la UCLA con una beca Fulbright. En 1994, cofundó La Panadería con el artista Miguel Calderón, un espacio de exhibición para artistas mexicanos emergentes que utilizan medios no convencionales. Actualmente, colabora con otros artistas para dirigir SOMA, un grupo de investigación artística que explora las posibilidades del arte en diferentes contextos.

Las obras de Okón, que incluyen videoinstalaciones, fotografía, performances y más, se han exhibido en todo el mundo y forman parte de importantes colecciones como la Tate Modern, el Museo de Arte del Condado de Los Ángeles, la Colección Jumex y otras . El año pasado, su pieza colaborativa " Demo" con el profesor de la ASU Juan Obando se exhibió en el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Tucson .

“Con un enfoque amplio, su obra difumina la frontera entre la realidad y la ficción, examinando contradicciones y absurdos que revelan los mecanismos que subyacen a la política, los sistemas de mercado y las ideologías neoliberales. Su obra critica los sistemas de poder e interroga cómo entendemos la realidad, la verdad y la autonomía”, declaró el profesor David Taylor, decano asociado de Asuntos Académicos, sobre la obra de Okón.

“En general, me considero una persona feliz y disfruto mucho de la vida, pero también noto mucha violencia a mi alrededor. Creo que el capitalismo neoliberal es un sistema muy violento, por eso en mi trabajo me interesa abordar la violencia sistémica más allá de las narrativas oficiales que suelen explicarla de forma simplista y engañosa”, dijo Yoshua Okón.

Okón comenzó la conferencia presentando uno de sus primeros trabajos de la década de 1990, "Oríllese a la Orilla", una serie de videos de policías mexicanos. Cada video no tenía guion ni ensayo, y se grabó en una sola toma. Okón invitó a los policías a su estudio para participar en una pelea, y a otro a actuar con su porra, después de verlo jugando con ella en la calle. Les ofreció pagarles, y uno aceptó participar en el video con la condición de insultar a Okón. "Bueno, en general, nos gusta estar frente a las cámaras, lo disfrutamos. O sea, miren el mundo de hoy", respondió Okón después de que le preguntaran sobre la motivación de cada policía para participar en la serie.

Según Okón, el formato vertical apenas existía en ese momento, pero los filmó así para la instalación y para cómo serían vistos. Siempre se había preguntado cómo usar el video de una manera que generara participación, en lugar de cómo se consumía pasivamente. "Era muy importante crear esta tensión entre el documental y la realidad. Que el público se preguntara: '¿Qué tan real es esto?' [...] '¿Qué tan ficticio es lo que estoy viendo?'. En realidad, son ambas cosas. Es muy artificial, por supuesto, y les pido que vengan a mi estudio, pero al mismo tiempo, no tengo el control total, no hay guion", dijo Okón sobre "Oríellese a la Orilla".

La siguiente pieza que Okón compartió fue de 2011, titulada "Pulpo". Esta fue creada casi una década después de obtener su maestría en Bellas Artes, cuando fue invitado por el Museo Hammer de Los Ángeles a realizar una residencia de investigación. Esta pieza está inspirada en los jornaleros indocumentados que consiguen trabajo en los estacionamientos de Home Depot y en lo que leyó sobre la guerra civil guatemalteca. La obra muestra a un grupo de exguerrilleros recreando la guerra civil en la que lucharon, en el estacionamiento de Home Depot.

Consistía en muchos ensayos donde los actores mostraban los movimientos que utilizaban en la guerra, y luego creaban una coreografía para ser interpretada en el estacionamiento, sobre el cual no tenía control.

“La sensación que percibí fue que estaban entusiasmados por participar en algo que trataba sobre quiénes son, su historia. Casi nadie sabe que Estados Unidos invadió Guatemala y cómo eso se relaciona con su presencia aquí ahora. Estaban entusiasmados por ser parte de esto […] y, para ser honestos, la tensión del rodaje tenía más que ver con ser expulsados del estacionamiento que con cualquier otra cosa”, dijo Okón. “Cuando hice esta pieza, quería hablar sobre la migración forzada, en el contexto de la geopolítica, la política exterior estadounidense y, sobre todo, el contexto del capitalismo global y este tipo de violencia que nos es invisible y que está en gran medida detrás de la migración forzada […] Quería darle esa dimensión a la guerra, en contraposición a la glorificación de la guerra que nunca ofrece una visión completa”.

A continuación, Okón habló sobre “Oracle”, una pieza que realizó en 2014 en Oracle, Arizona, tras recibir una invitación del Museo de Arte de la ASU para producir una nueva obra y realizar una exposición. Esta pieza se inspiró en la noticia de la llegada de niños no acompañados a Estados Unidos desde Centroamérica y en la noticia de una gran protesta en Oracle para proteger la frontera. Concibió esta pieza como una segunda parte de “Octopus”, y los actores recrearon su protesta. “Hay una especie de aspecto orgánico en la forma en que se crean estas obras porque suelo trabajar con lo que encuentro en el mundo […] y a partir de ahí, construyo. Y en diferentes casos, el grado de ficción puede variar según las ideas que se me ocurran y las particularidades de la situación”, dijo Okón. Al comenzar una obra, siempre se acerca a las personas como artista y explica el contexto de la obra y la exposición.

Por cuestiones de tiempo, la noche terminó brevemente con el estreno de la nueva pieza de Okón, que acababa de fotografiar y editar. "Espero que, a través de mi arte, la gente reflexione sobre los temas que presento [...]. No me interesa que lleguen a ninguna conclusión específica, pero me gusta el proceso reflexivo en sí mismo, la expansión de la conciencia y la comprensión del mundo de formas más complejas y matizadas. Esa es una de las principales razones por las que hago arte", dijo Okón.