'La Petite Mort' by Gabriel de la Mora

‘La Petite Mort’ de Gabriel de la Mora

Until February 8, the Jumex Museum presents an exhibition that highlights two of the essential themes of this Mexican artist: death and ecstatic sexual pleasure.

Hasta el 8 de febrero, el Museo Jumex presenta una exposición en la que se advierten dos de los motivos esenciales de este artista mexicano: la muerte y el placer sexual extático.

23.1.2026

By Sergio Briceño for Milenio

Por Sergio Briceño para Milenio

One of the most emblematic elements of the work of Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico City, 1968) is undoubtedly the color black, which is actually the absence of color, but which in the background constitutes one of the discursive paths of an artist who has set out from the beginning to strip the everyday world of its conventional scaffolding .

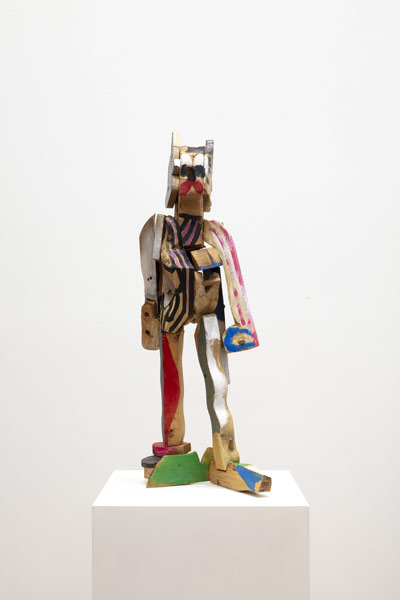

Hence, from the blackness of his work, his searches for immateriality and transience culminated in a charred page of his undergraduate thesis, which is simultaneously the sum of the ephemeral and the timeless, a domestic black hole in which the two dimensions that interest the author continue to flow: present life and the mutability of other possible lives . Hence, anxieties arise within him that crystallize both in beating himself as if he were a piñata, made of cardboard in his own likeness, and in searching for himself in an endless list of people who share his name: Gabriel de la Mora, a surname that everyone in Colima, where his family is from, knows and which includes among its most illustrious members the martyr and saint Miguel de la Mora, whose assassination at the hands of Plutarco Elías Calles's government sparked the Cristero War in the late 1920s across almost the entire country.

This idea of the religious almost invisibly articulates Gabriel's proposals, who seeks in geometric and abstract forms an explanation, or at least an approach, to the mechanics that sustain us as human beings. Evidence of this lies in the worn materials— ceilings, old furniture—that he subjects to the action of time and the elements, as if trying to demonstrate that the soul is polished in adversity and that the wonders of existence are invisible , as well as ever-changing. The edges and angles have to fit together in a world of curves and ellipses, that's why the eggshells, already in thousands of fragments, tend to total a single axis, a single Pascalian center in his exercise to define God, and the same happens with the skulls of a part of his family, including that of a dead girl, where he tries to synthesize in white —the sum of all colors—, the pain that includes the joy of being part of a family and he in particular as the son of a well-known freed priest in Colima who had the same name as him: Gabriel de la Mora.

Transgression, apostate interlude, and the idea of alternation in dislocation led Gabriel the artist to create an enormous labyrinth of concave mirrors that invert the human image, distort it, intersect it, just like a gigantic panel made of broken speakers, where the metaphor of the nonexistent and the fleeting is recalled, in this case sound, that music that has passed through the meshes that protect the speakers, leaving an undetectable residue, subatomic particles of a bolero, a Metallica riff or a danzón, hence the phrase "What we don't see, what looks at us", which here could be changed to "What we don't hear, what hears us" , as happens with some pieces of "Originally False", a series where Gabriel transforms fake paintings into his own works, by intervening and handling them to increase the erasure.

Perhaps the piece that best encapsulates much of Gabriel's exploration in this gloss of his, exhibited at the Jumex Museum under the title La Petite Mort , is the monumental obsidian mirror that recalls Bernardo Esquinca's text on the Reflecting God . This text not only revolves around Tezcatlipoca, perhaps the central deity of everything related to that obsidian which invites us to other worlds, but also around the numerous possibilities of other options when creating a work. In this case, however, it is summarized in a hyperfragmentation of the Self; that is, the unity that we are and that defines us is reduced to its smallest, most elemental element. Because of the impossibility of creating an obsidian mirror, that smoking mirror to which Carlos Fuentes alluded and which Rubén Bonifaz Nuño christened the reflection of a flame, Gabriel opts for the splinter, that flake that seduced Salvador Díaz Mirón and that It is always automatically associated with that desire to reach the Whole through the Parts. And in the spiral of all that, the butterfly, a consolidated symbol of Tlaltecuhtli, that elusive Mexica goddess so closely linked to her aspect, precisely Itzpapálotl who united heaven and earth, that obsidian butterfly that synthesizes the cycle of what is born and dies and is reborn, like the geometric cycles of Gabriel de la Mora: impalpable cutting , symmetrical, sharp cycles, like those necessary, indispensable knives for extracting the heart.

Uno de los elementos más emblemáticos de la obra de Gabriel de la Mora (Ciudad de México, 1968) es sin duda el color negro, que en realidad es ausencia de color, pero que en el fondo constituye una de las vías discursivas de un artista que se ha planteado desde un primer momento despojar del andamiaje convencional al mundo cotidiano.

De ahí que a partir del negro las búsquedas de inmaterialidad y fugacidad terminaran en una hoja carbonizada de su tesis de licenciatura, lo que es a un mismo tiempo la suma de lo efímero y lo atemporal, un doméstico hoyo negro en el que siguen fluyendo las dos dimensiones que le interesan al autor: la vida presente y la mutabilidad de otras posibles vidas. De ahí que surjan en él inquietudes que lo mismo cristalizan en apalearse a sí mismo como si se tratara de una piñata, elaborada en cartón con su propio aspecto, que en buscarse en una lista infinita de personas que se llaman como él: Gabriel de la Mora, un apellido que en Colima, de donde es su familia, todos conocemos y que incluye entre sus miembros más insignes al mártir y santo Miguel de la Mora, cuyo asesinato a manos del gobierno de Plutarco Elías Calles desató la Cristiada a finales de los años veinte en casi todo el país.

Esta idea de lo religioso articula de modo casi invisible las propuestas de Gabriel, quien busca en el geometrismo y lo abstracto una explicación o al menos un acercamiento a la mecánica que nos sostiene como seres humanos. Prueba de esto son los materiales luidos, plafones, muebles viejos, que somete a la acción del tiempo y la intemperie como si intentara demostrar que el alma se pule en la adversidad y que las maravillas de la existencia son invisibles, además de cambiantes. Los filos y los ángulos tienen que ensamblar en un mundo de curvas y de elipses, por eso los cascarones de huevos, ya en miles de fragmentos, tienden a totalizar un solo eje, un solo centro pascaliano en su ejercicio por definir a Dios, y lo mismo ocurre con los cráneos de una parte de su familia, incluyendo el de una niña muerta, donde trata de sintetizar en blanco —la suma de todos los colores—, el dolor que incluye la alegría de ser parte de una familia y él en particular como hijo de un sacerdote manumiso muy conocido en Colima y que llevaba su mismo nombre: Gabriel de la Mora.

La transgresión, el interludio apóstata y la idea de alternancia en la dislocación llevaron al Gabriel artista a crear un enorme laberinto de espejos cóncavos que invierten la imagen humana, la distorsionan, la intersectan, lo mismo que un gigantesco panel a base de bocinas rotas, donde se recuerda la metáfora de lo inexistente y lo fugaz, en este caso el sonido, esa música que ha atravesado por las mallas que protegen a los bafles, dejando un residuo indetectable, partículas subatómicas de un bolero, un riff de Metallica o un danzón, de ahí la frase “Lo que no vemos, lo que nos mira”, que aquí podría cambiarse por “Lo que no escuchamos, lo que nos oye”, como ocurre con algunas piezas de “Originalmente falso”, serie donde Gabriel transforma pinturas falsas en obras suyas, al intervenirlas y manejarlas para aumentar la borradura.

Quizás la pieza que resume buena parte de las búsquedas de Gabriel en esta glosa suya que bajo el título de La Petite Mort se exhibe en el Museo Jumex, sea el monumental espejo de obsidiana que nos recuerda el texto de Bernardo Esquinca sobre el Dios Reflectante, que no solo gira en torno a Tezcatlipoca, acaso el numen central de todo lo relacionado con esa obsidiana que invita hacia otros mundos, sino también en derredor de la numerosísima posibilidad de otras opciones a la hora de ejecutar una obra, pero que en este caso se resume en una hiperfragmentación del Yo, es decir, la unidad que somos y que nos define, queda reducida a su elemento más ínfimo, más elemental, porque en función de la imposibilidad de crear un espejo de obsidiana, ese espejo humeante al que aludió Carlos Fuentes y que Rubén Bonifaz Nuño bautizó como el reflejo de una flama, es que Gabriel opta por la esquirla, esa lasca que sedujo a Salvador Díaz Mirón y que se asocia siempre, de manera automática, con ese deseo de llegar al Todo mediante las Partes. Y en la espiral de todo eso, la mariposa, símbolo consolidado de la Tlaltecuhtli, esa diosa mexica tan evasiva y tan hermanada con su advocación, justamente la Itzpapálotl que juntaba el cielo con la tierra, esa mariposa de obsidiana que sintetiza el ciclo de lo que nace y muere y vuelve a nacer, como los ciclos geométricos de Gabriel de la Mora: impalpables ciclos cortantes, simétricos, filosos, como esos cuchillos necesarios, indispensables, para extraer el corazón.