Gabriel de la Mora explores the meanings of death in the Museo Jumex's major autumn project.

Gabriel de la Mora explora los sentidos de la muerte en la gran apuesta del Museo Jumex para el otoño

The contemporary art center in Mexico City presents its new season catalog, which includes an exhibition by Elsa-Louise Manceaux and a documentary retrospective by Italian artist Tina Modotti.

El centro de arte contemporáneo en la capital mexicana presenta el catálogo de la nueva temporada, que incluye una muestra de Elsa-Louise Manceaux y una retrospectiva documental de la italiana Tina Modotti

24.9.2025

By: Elena San José for El País Online

Por: Elena San José para El País Digital

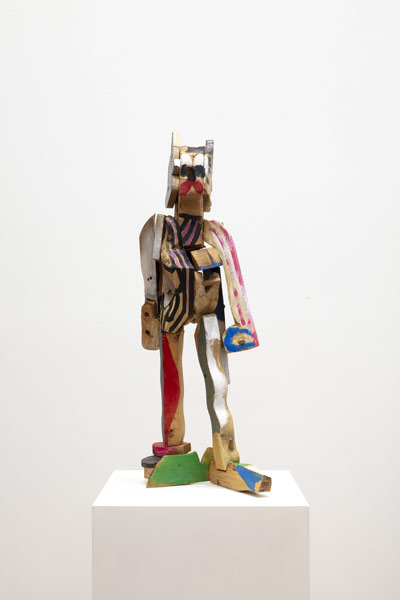

Gabriel de la Mora (Mexico City, 1968) says his dyslexia is at the root of his interest in all points of view, in the duality of objects and reality. For example, the Mexican artist notes, he is fascinated by the thought that a human being can die before even being born, as happened to his sister, who died in her mother's womb before seeing the light. The reverse also happens, he adds. Objects that died long ago, when they ceased to fulfill the function for which they were created, suddenly take on a new life through their manipulation. His art pivots on this idea. "For many, death is the end of something; for me, it's the beginning. I like how a work can be created 130 years before I was born," the artist summarizes. His exhibition, *La petite mort* (The Little Death ), composed of 87 works spanning more than 20 years of work, is the Museo Jumex's major exhibition this fall in Mexico City. The contemporary art center inaugurated it this Wednesday along with the rest of the season's catalog, which includes an exhibition by French artist Elsa-Louise Manceaux, a documentary retrospective by Italian artist Tina Modotti, and the Jumex Collection, which features works recently acquired by the gallery.

The exhibition's title nails the core of that duality. "Little death" is the French euphemism for orgasm, "the feeling of abandonment or loss that physical pleasure can provoke at its peak," according to the exhibition's presentation. "Orgasm is the only instant in which a human being doesn't think. It's a second where time also extends into something much longer," notes De la Mora, drawing an analogy between the two types of death. For Tobias Ostrander, the exhibition's curator, the idea was "to raise questions about what kind of obsessions lie behind the work, trying to confuse or conflate aesthetic pleasure with erotic pleasure ." The intended effect refers to the "pleasure of the text" spoken of by the French writer Roland Barthes, who considered la petite mort an aspiration of all artistic expression.

The exhibition, structured in six parts— Bodies, Erasure, Heat, The Edge of Desire, Touch, and The Viewer's Pleasure —uses diverse techniques and materials to achieve this. Some border on the eccentric, such as the 3D printing of 17 human skulls belonging to his family, based on CT scans of their biological members. The installation required him to exhume and scan the tiny remains of his sister and the half-decomposed remains of his father, both deceased. The list, however, is long. There are ceramic tiles broken by the weight of De la Mora's body itself, hairs belonging to his relatives, fabrics mounted on wood, fragments of composite panels on linen or aluminum, shoe soles, thousands of pieces of obsidian, Post-it notes, and naturally dead butterfly wings. There are also papers burned until they are almost charred, but not enough to disintegrate.

“It's such a fragile, yet eternal work, that a photographer felt the tension of thinking that the flash could destroy it. I find those kinds of tensions marvelous,” the artist explains. The series of burned papers marks the starting point where the Mexican artist began to let go of the need to control his work. “I would initiate an action, and everything else happened at random,” he says. “I began to discuss with the restorers what the conditions are conducive to art. If we're investing so many resources into maintaining something in certain conditions, what happens if we do exactly the opposite? If we have to control humidity, let's expose it to hail, rain, ash from the Popocatépetl volcano, and see what happens,” he explains. “The results were extraordinary.”

The results include deeply abstract works and others that give rise to portraits where the human form is clearly distinguished against its surrounding background. All of this without losing sight of the legacy of his architectural training. “I left architecture 30 years ago, but I knew I had to return to it, not as an architect, but as an artist,” says De la Mora. He has the very architecture of the museum at his disposal: the entire top floor of the contemporary art center, which houses his work from this Thursday until February 8.

Dice Gabriel de la Mora (Ciudad de México, 1968) que su dislexia está en el origen de su interés por todos los puntos de vista, por la dualidad de los objetos y de la realidad. Por ejemplo, señala el artista mexicano, le fascina pensar en que un ser humano pueda morir antes siquiera de haber nacido, como le ocurrió a su hermana, que falleció en el vientre de su madre antes de ver la luz. También sucede a la inversa, agrega. Objetos que murieron tiempo atrás, cuando dejaron de cumplir la función para la que habían sido creados, de repente cobran una nueva vida a través de su manipulación. Sobre esa idea pivota su arte. “Para muchos la muerte es el final de algo, para mí es el inicio. Me gusta cómo una obra puede ser creada 130 años antes de que yo naciera”, sintetiza el creador. Su exposición La petite mort (La muerte pequeña), compuesta de 87 obras que abarcan más de 20 años de trabajo, es la gran apuesta para este otoño del Museo Jumex, en la capital mexicana. El centro de arte contemporáneo la ha inaugurado este miércoles junto con el resto del catálogo de la temporada, que incluye una muestra de la francesa Elsa-Louise Manceaux, una retrospectiva documental de la italiana Tina Modotti y la Colección Jumex, que cuenta con las obras adquiridas recientemente por la galería.

El título de la muestra se clava en el centro de esa dualidad. La “muerte pequeña” es el eufemismo con el que se hace referencia en francés al orgasmo, “al sentimiento de abandono o pérdida que puede provocar el placer físico en su punto álgido”, según se lee en la presentación de la muestra. “El orgasmo es el único instante en el que un ser humano no piensa. Es un segundo donde el tiempo también se extiende a algo mucho más prolongado”, apunta De la Mora, haciendo una analogía entre los dos tipos de muerte. Para Tobias Ostrander, curador de la exposición, la idea era “abrir preguntas sobre qué tipo de obsesiones hay detrás de la obra, tratando de confundir o mezclar el placer estético con el placer erótico”. El efecto buscado remite al “placer del texto” del que hablaba el escritor francés Roland Barthes, que consideraba la petite mort una aspiración de toda expresión artística.

La muestra, estructurada en seis partes —Cuerpos, Borradura, Calor, El filo del deseo, Tacto y El placer del espectador— se sirve de diversas técnicas y materiales para lograrlo. Algunas rozan lo excéntrico, como la impresión en 3D de 17 cráneos humanos, correspondientes a su familia, a partir de tomografías de los miembros biológicos. La instalación requirió que exhumara y escaneara los diminutos restos de su hermana y los restos medio descompuestos de su padre, ambos fallecidos. La lista, sin embargo, es larga. Hay baldosas de cerámica rotas por el propio peso del cuerpo de De la Mora, pelos de sus familiares, telas montadas sobre madera, fragmentos de plafones compuestos sobre lino o aluminio, suelas de zapatos, miles de pedazos de obsidiana, de post-its o de alas de mariposa muertas de forma natural. Hay, también, papeles quemados hasta quedar casi carbonizados, pero no lo suficiente como para desintegrarse.

“Es una obra tan frágil, pero también eterna, que a un fotógrafo le generó la tensión de pensar que la luz del flash pudiera destruirla. Ese tipo de tensiones se me hacen maravillosas”, expone el artista. La serie de papeles quemados marca el punto de inicio en el que el creador mexicano comenzó a desprenderse de la necesidad de controlar su obra. “Yo iniciaba una acción y todo lo demás ocurría al azar”, dice. “Empecé a ver con los restauradores cuáles son las condiciones propicias para el arte. Si estamos invirtiendo tantos recursos en mantener algo en ciertas condiciones, ¿qué pasa si hacemos exactamente lo opuesto? Si tenemos que controlar la humedad, vamos a exponerlo al granizo, a la lluvia, a la ceniza del volcán Popocatépetl, y ver qué sucede”, desarrolla: “Los resultados fueron extraordinarios”.

Los resultados incluyen obras profundamente abstractas y otras que dan lugar a retratos donde la forma humana se distingue claramente sobre el fondo que la contiene. Todo ello, sin perder de vista la herencia que le dejó su formación arquitectónica. “Dejé la arquitectura hace 30 años, pero supe que debía regresar a ella, no como arquitecto, sino como artista”, dice De la Mora. A su disposición tiene la propia arquitectura del museo: la última planta al completo del centro de arte contemporáneo, que alberga su obra desde este jueves y hasta el 8 de febrero.

Pics by Aggi Garduño

Fotos por Aggi Garduño