A conversation with Gabriel de la Mora about his work, transformation, patience, and his last 20 years of career

Una plática con Gabriel de la Mora sobre su obra, la transformación, paciencia y sus últimos 20 años de carrera

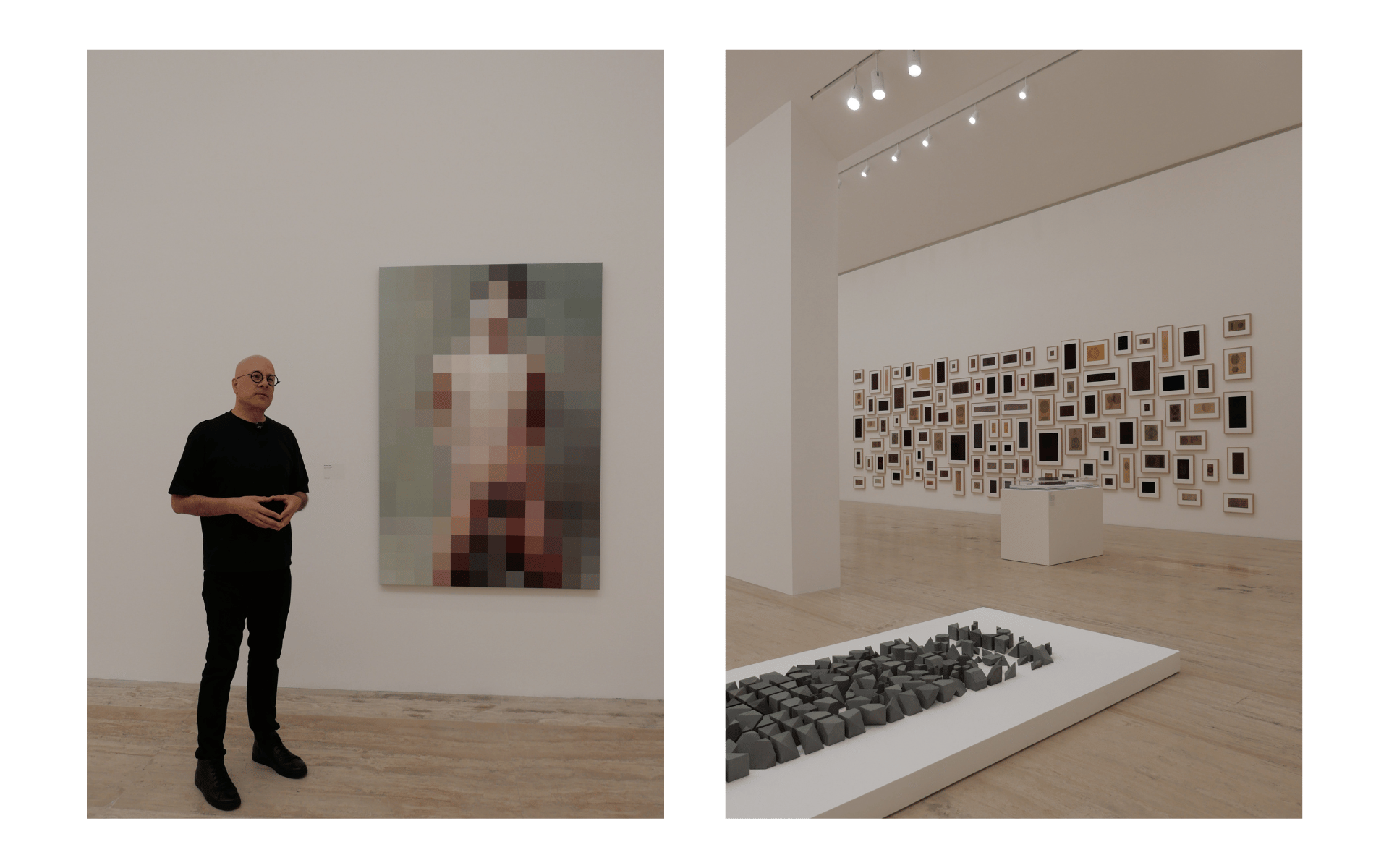

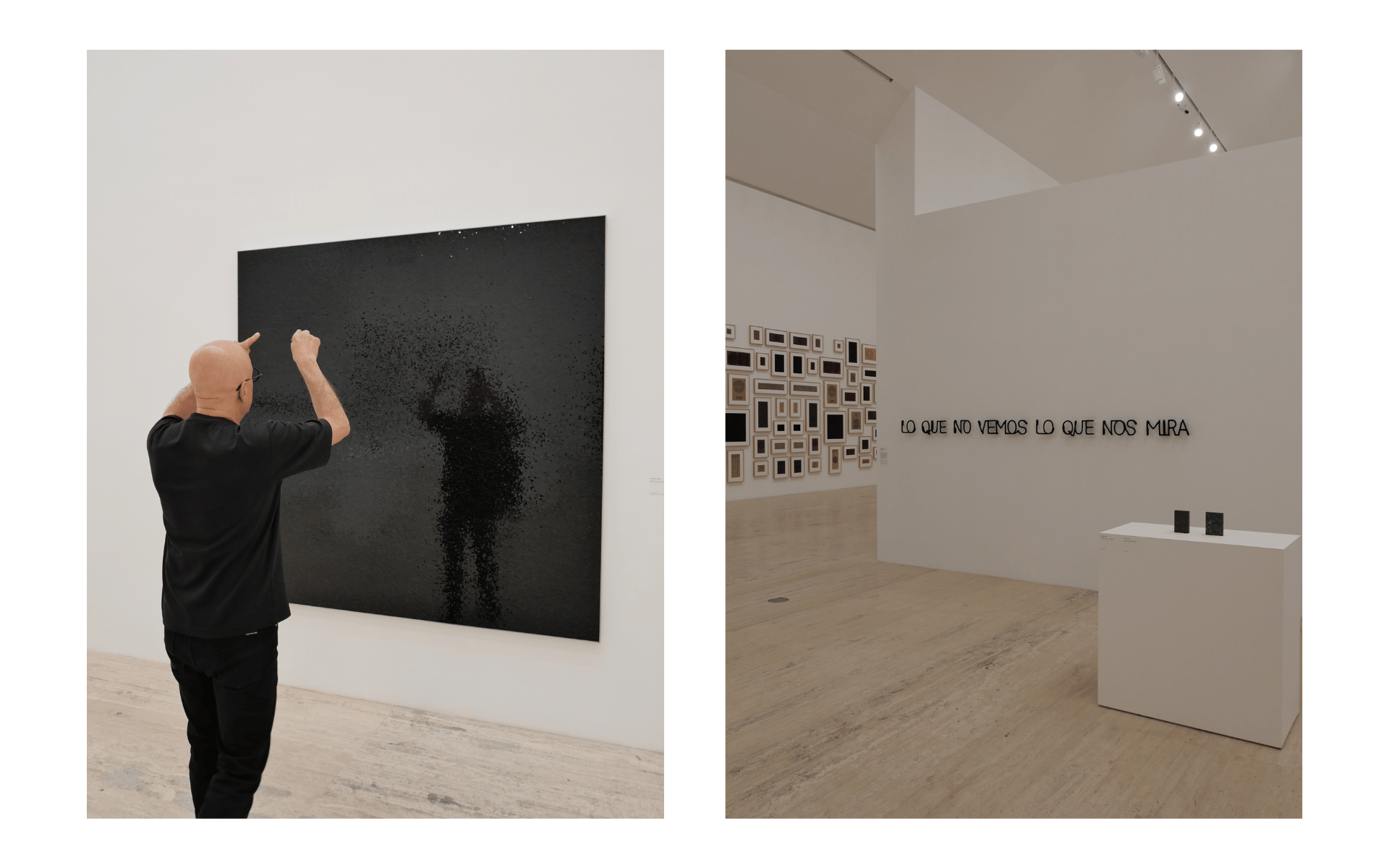

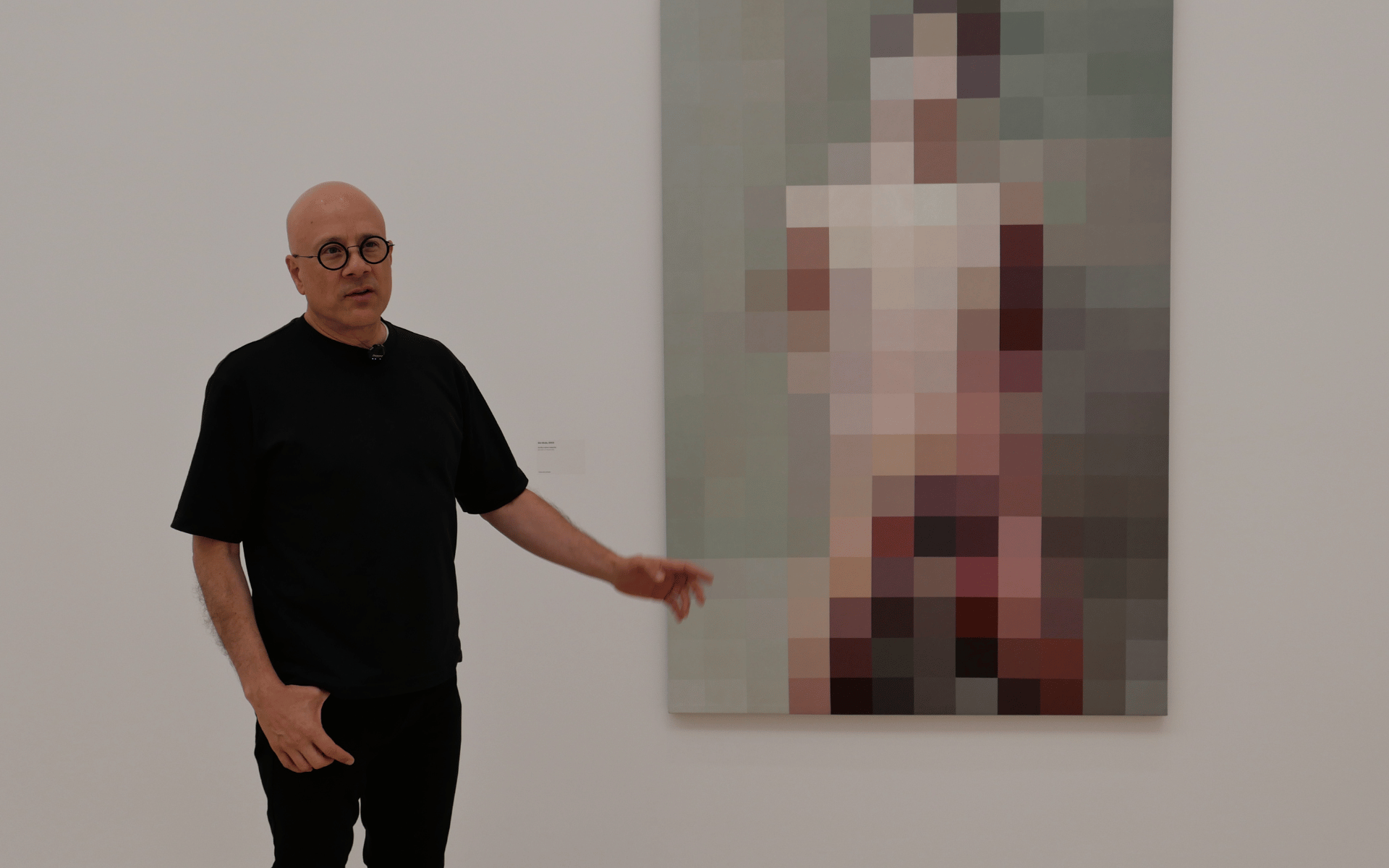

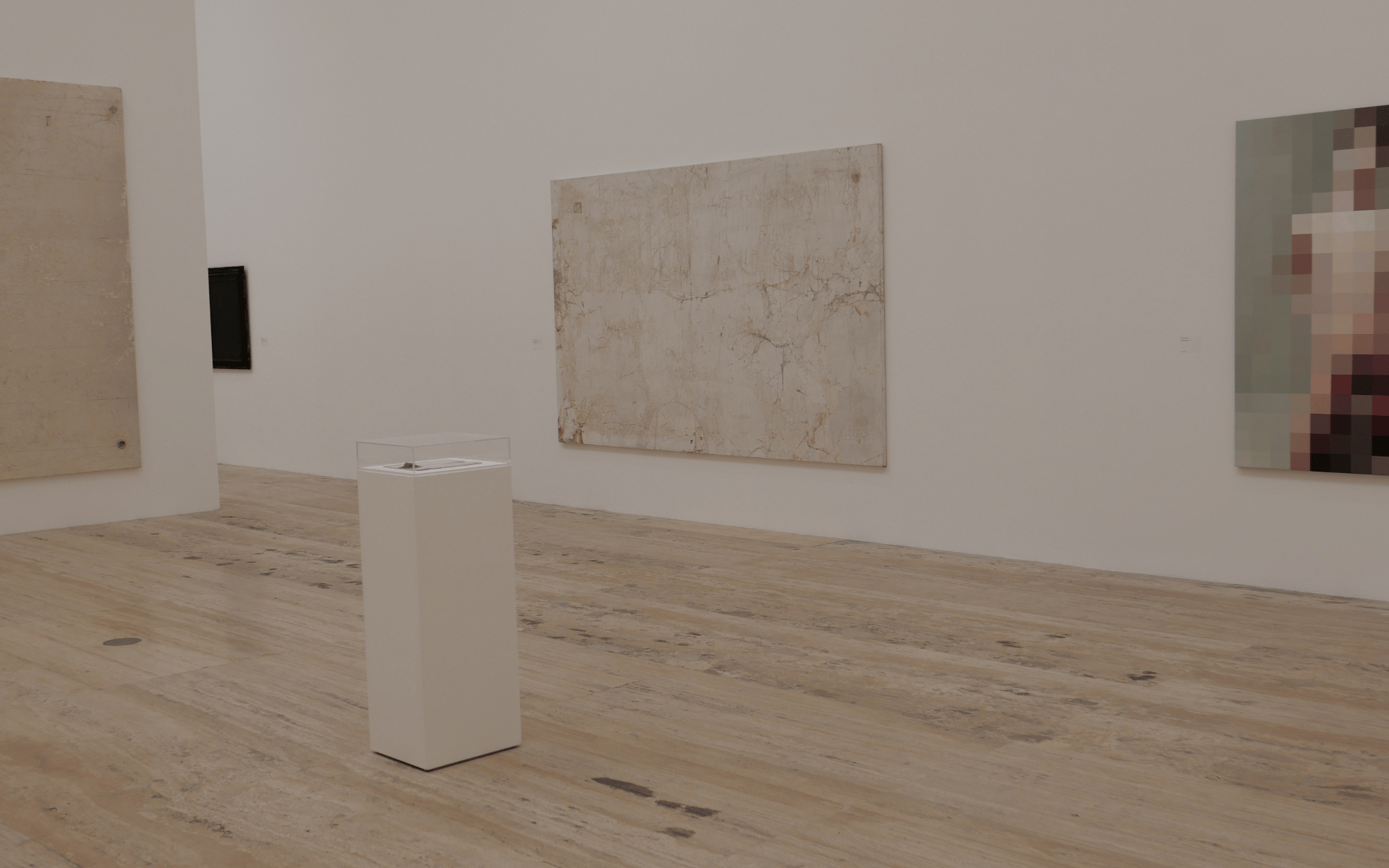

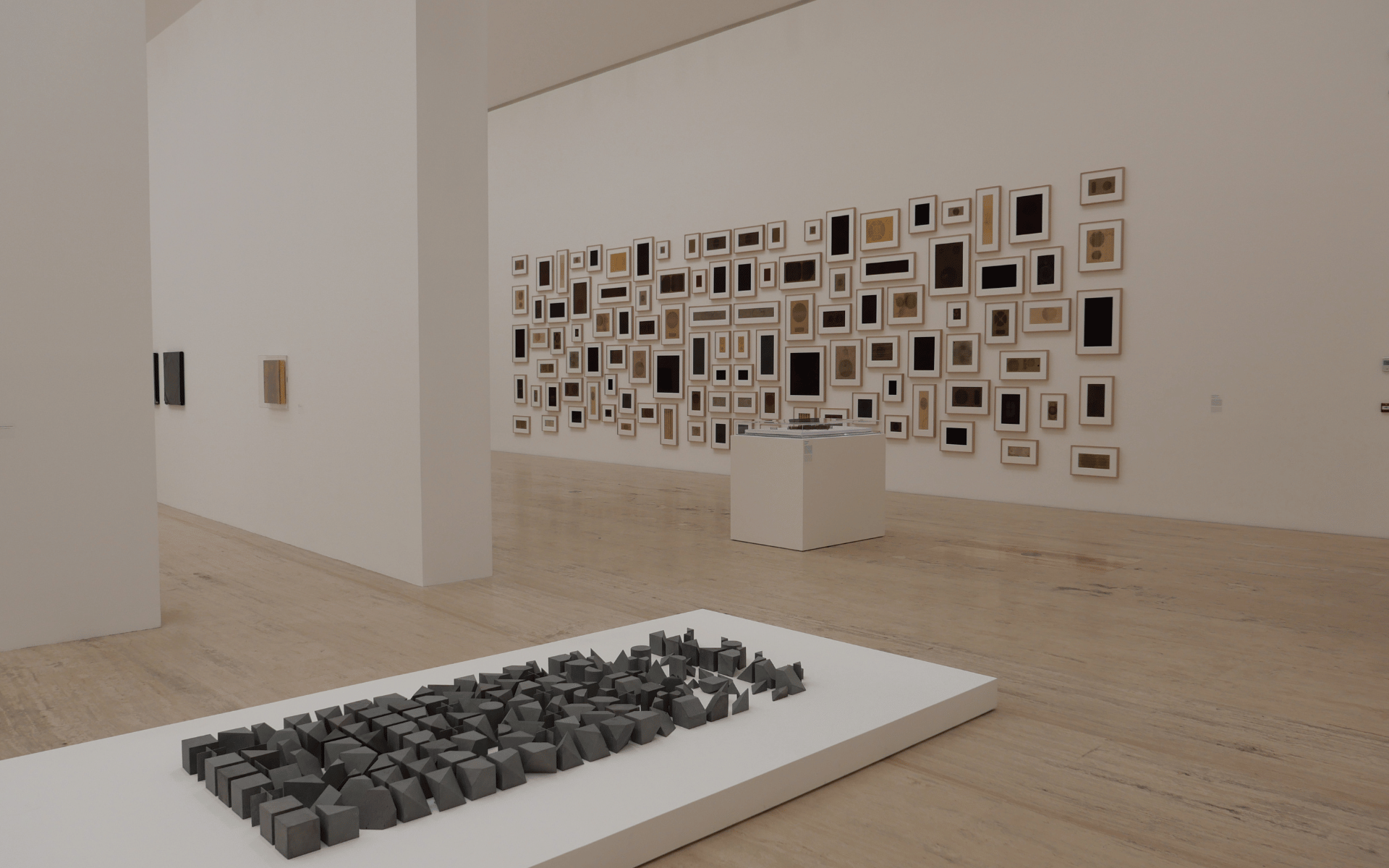

La Petite Mort, Gabriel de la Mora's new exhibition at the Museo Jumex, reveals the processes, obsessions, and transformations that have guided 30 years of his career. An intimate look at his practice through desire, loss, and matter.

La Petite Mort, la nueva exposición de Gabriel de la Mora en el Museo Jumex, revela los procesos, obsesiones y transformaciones que han guiado 30 años de su carrera. Una mirada íntima a su práctica a través del deseo, la pérdida y la materia.

5.12.2025

By: Estefanía Fink for Local MX

Por: Estefanía Fink for Local MX

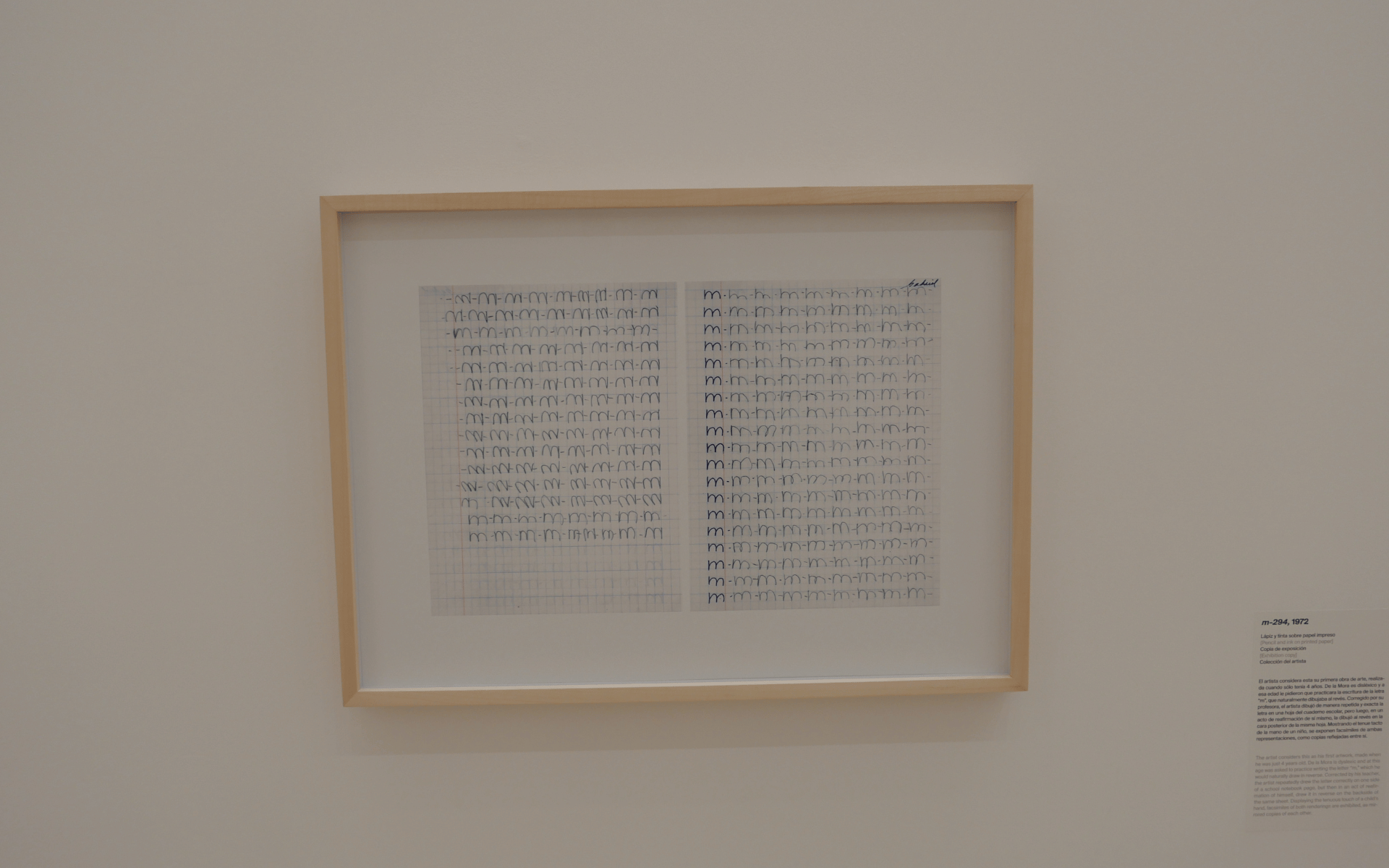

“Something that impacted me enormously was discovering that the first piece I made, at the age of four in 1972, is connected to all my work from these first 30 years of my career,” Gabriel de la Mora told us when we spoke with him about the retrospective of the last 20 years of his career currently on display at the Jumex Museum.

And that phrase—spoken with the serenity of someone who has spent decades classifying, counting, dissecting, and transforming matter as if rereading his own life—summarizes the spirit of La Petite Mort better than anything else.

The exhibition not only spans two decades of work, but also allows us to see for the first time the underlying thread that connects it: an obsessive drive to reveal what remains when something wears down, burns, is cut, or is lost; her obsession with transformation and the patience that characterizes her work. Curated by Tobias Ostrander, the exhibition unfolds as a journey through different states of desire and disappearance: of the body offered as a surface, of the skin that archives memory, of the material that dies to transform into something else.

In these rooms, Gabriel de la Mora confirms something that in his studio seems almost a physical law: “art is neither created nor destroyed, it is only transformed .” And in changing, he also exposes the artist. Because looking closely at these pieces—sometimes so meticulous that they force the body to approach almost to the point of holding its breath—is to look at the compulsion, the patience, the mental levitation, and the intimate archive that sustain his work.

La Petite Mort is an exhibition about loss, yes. But also about how that loss becomes knowledge, aesthetic pleasure and, above all, continuity: an unexpected bridge between a drawing made by a four-year-old child and an artist who, more than thirty years later, continues to strive to keep his work suspended in the air… without touching the ground.

What kind of “loss” do you seek to provoke in the viewer with your work?

Whenever something is lost, something is gained. By losing matter, for example, new information is revealed: wear and tear, an action, time. Loss thus becomes another form of knowledge.

I mean perhaps that in this world everything that exists is here to fulfill a function or a service; when this ends, the end of something can transform into the beginning of something else.

My definition of art is a parallel to the definition of energy: Art is neither created nor destroyed, it is only transformed.

The title suggests both pleasure and extinction. Is there a point where desire and death become indistinguishable for you within the artistic process?

The exhibition's title, "La petite mort" or "Little Death," was chosen by curator Tobias Ostrander. Citing an article written by Susan Crowley about the exhibition, he shares the following: "For Georges Bataille, ' la petite mort' does not refer to the physical act of dying; it is a metaphor for the extreme experience where consciousness is momentarily suspended by intense pleasure."

Tobias somehow points towards physical and aesthetic pleasure.

Death marks the end of something, which at the same time marks the beginning of something else through transformation.

Your processes are full of sorting, dissecting, counting, and accumulating. What part of your psyche is activated when you engage in that extreme meticulousness?

I don't know if "obsession" or "repetition" would be the answer to this question, but the process is very important to me in everything. Classification and archiving are another essential part of my work: everything that happens before or during the transition from an idea to a piece or a work is something the public generally doesn't see, and I like to document it in various ways; these notes and records form part of the archive for each piece or series.

Repetition, in reality, does not exist: there will never be two identical things, because differences always arise in every attempt. As Gilles Deleuze says in his book Difference and Repetition (1968), which, curiously, is also my birth year, every repetition is, in itself, a variation.

I noticed that something that characterizes your work is patience, which seems to operate almost as a parallel mental state. What have you discovered about yourself in those processes of your work that only exist in slowness?

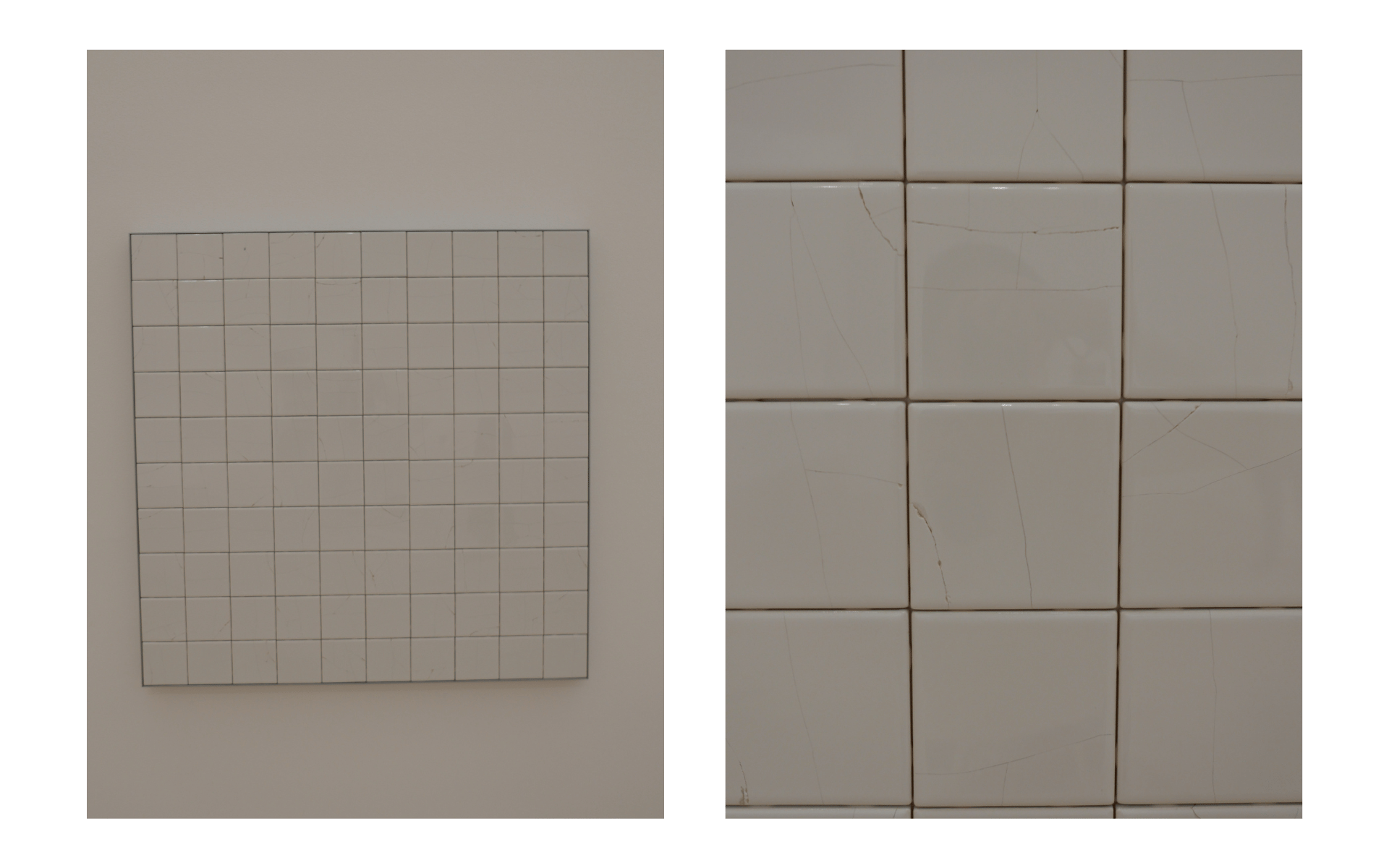

Patience is one of the many key elements in my work, and this becomes evident when I place hundreds or thousands of eggshell fragments onto a wooden panel, counting each one. In the end, the total number of fragments on the surface will be the title of the work—a number only revealed upon completion.

Doing a job that requires concentration and involves repeated actions leads you to a state close to meditation, and that's precisely where a large number of ideas appear, which are noted down and wait for the moment to be explored and executed.

Working in the studio is similar to meditating, and all of this leads to what you mention in the question, to levitation or slowness among many other elements or factors.

The silence, activated by the click of each counter when each fragment is pasted, generates a very special state: a continuous note to infinity, a state in which any color disappears leaving an absolute white surrounded by ideas, I don't know if time stops or disappears, I don't know if in this state one breathes and this somehow makes real one of the many dreams I have had since childhood: it is to fly and walk without touching the ground, slow and cold.

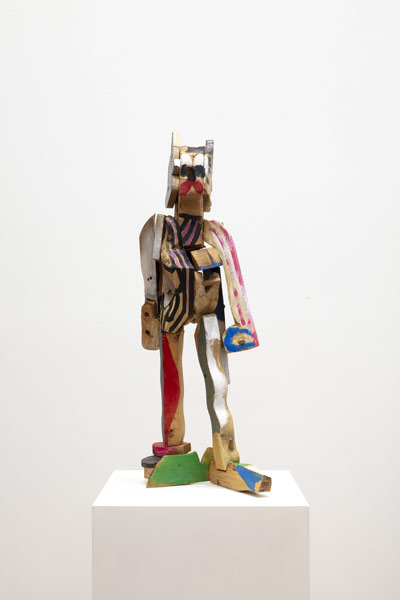

What attracts you to materials that others would consider waste? Are you interested in their history, their energy content, or their status as residue?

Waste is something that has fulfilled its original function and is about to be thrown away or disappear. All these materials contain information about the action or purpose they once served; they carry their own energy. Through various processes, and with the support and guidance of restorers, I halt this deterioration: they are consolidated to extend the life of these materials transformed into art, preserving them for as long as possible and in the best possible condition.

I seek to answer all the questions that arise in each material that attracts me and that I begin to collect. I'm also interested in how an idea can lead to a work of art, how a group of works can generate a series, and sometimes even a new technique . When that happens, for me, the perfect series or pieces emerge. I love getting excited about certain ideas, but I enjoy it even more when the results surpass all expectations and end up being so much more than I could have imagined or hoped for.

You say that the artist neither creates nor destroys, but transforms. What made you let go of the romantic idea of the artist as a “creator”?

The same thing that has led me to question everything about authorship, in the end the only thing that matters and the only thing that will always exist will be the work of art that will constantly change until it disappears; and when this happens it will transform into something else.

That's why I maintain that in the pyramid of art there are only four letters: those of ART or WORK, since everything else, including the artist, will disappear. That's why the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City is my favorite museum, one I try to visit constantly. There, no names exist, no artists; the wood and stone carvings have lost their color, their polychromy, and yet they remain masterpieces, sometimes even avant-garde.

How does your work engage with the idea of skin: as a border, as an archive, or as a surface of desire?

Skin is a subject that has always interested me, and perhaps that's why I arrived at the series of paintings in which I mix my blood with varnish in successive layers until I achieve the tone of my skin, then apply various cuts with a razor blade. In a way, this generates self-portraits and connects with the beginnings of painting, even evoking cave paintings.

I am drawn to the idea of skin as a border, as an archive and also as a surface of desire: the line that divides the inside from the outside, life from death.

Some pieces require almost intimate proximity to be seen. What does it mean to you to bring the viewer's body close to a microscopic scale?

I'm fascinated by the idea of the viewer approaching the artwork without touching it. When this happens, the pieces are activated, and somehow the energy of those looking at them is absorbed by the materials and the artwork itself. All of this is stored as information, and the audience, in a way, becomes part of the piece.

If death is latent in your processes, what does it mean for you to make works that end up entering collections and museums, where they are "preserved"?

At the beginning of my career, I kept everything I made; I liked to control and preserve each piece in its best condition. I found it very difficult to let go of, give away, sell, or release works, because I was afraid they would be damaged or even lost.

Over time I learned to let go, because it also excites me when someone likes a piece or my work and wants to own it, buy it, and, thanks to that, allows me to live from what I love most: being an artist and making art.

Every piece that leaves the studio has to sting a little. Sometimes, when a piece doesn't sell and comes back to me, I love seeing it again and having it as part of my collection. The only reason I would allow a piece to leave my collection is if a museum were interested in acquiring something from that series. That's one of the few ways a piece would cease to be mine: to become part of an institutional collection, to be exhibited, and to be engaged by the public. Furthermore, museums take exceptional care, which allows the works to remain in the best possible condition for as long as possible.

What role does compulsion play in your work? Is it a driving force, a method, or a consequence?

Everything and nothing at the same time. Compulsion, obsession, repetitive behaviors, passion, and intensity are some of the many characteristics that define me.

As Billy Elliot would say when trying to describe what dance is to him: electricity . Electricity is also a word that could answer this question: it is engine, method, impulse, and consequence.

I spend almost all my time in the studio. I only stop working for the day because I have to eat, sleep, and rest; otherwise, I'd be working and thinking 24/7. Sometimes I work out pieces or solve problems in my dreams; that's why I always have a notebook and pencil on my nightstand. Occasionally, I get up in the middle of the night to jot down an idea or work something out. Even when I'm walking or driving, I'm still working mentally, thinking, imagining pieces and series.

I usually only complete maybe 3% of everything I write. Inspiration comes from the work itself and from the ideas, and that continuous cycle is how I live, think, and work, whether I'm in the studio or at home.

After 20 years of work brought together in a single exhibition, what surprised you most about rediscovering yourself?

The 87 pieces in the exhibition span 22 years of my career, within a total period of 30 years (1996–2026). Many of the works in La Petite Mort are being exhibited for the first time.

Something that has surprised me greatly is that several collectors, critics, curators, and friends—people who have followed my work for years—have told me they thought they knew him, and that upon seeing the exhibition they realized they didn't really know him. They are moved and surprised, and hearing that makes me reflect deeply.

I see each exhibition as if it were my first; I'm thrilled that what I enjoy most about my work is what I'm doing now and what's to come . Of course, there will always be key pieces along the way, but I hope the day never comes when the best of my work is 10 or 20 years old. If that were to happen, I'd have to rethink everything… or perhaps consider retiring, although I've always believed that an artist doesn't retire: an artist's retirement is death.

Something that greatly impacted me was discovering that the first work I did, at the age of four in 1972, is connected with all my work from these first 30 years of my career.

And there was one piece that particularly shook me: Memory I , the family portrait made with skulls, from the Compass of Questions series (2007). I hadn't seen it for over ten years. During the installation, the supports and the 17 skulls were on the floor, ready to be set up. Seeing them there hit me hard.

David was filming the process, and with him were Kit Hammonds, curator of the Jumex Museum, and Tobias Ostrander, curator of the exhibition. I felt tears welling up; I stopped breathing for a moment and slowly backed away. David stopped filming, and suddenly there was absolute silence. As I stepped back and looked at Kit and Tobias, who were serious and staring at the floor, I burst out.

I was struck by the fact that the artwork depicted the skulls of my grandmother and mother, both of whom are no longer with us, and that deeply moved me. In a way, that piece sparked the beginning of the exhibition's installation, a project I initially didn't fully understand, but which, seeing it finished, I can say is the best exhibition I've presented to date.

Even so, every museum or gallery exhibition I've had has been impeccable and significant. And I hope that those to come will always be better than the last, just like my work and everything I do. I wish to never stop being excited and surprised, and to always remain happy… without losing sight of reality.

“Algo que me impactó enormemente fue descubrir que la primera obra que hice, a los cuatro años en 1972, está conectada con todo mi trabajo de estos primeros 30 años de carrera,” nos dijo Gabriel de la Mora cuando platicamos con él sobre la retrospectiva de los últimos 20 años de su trayectoria que actualmente se presenta en el Museo Jumex

Y esa frase —dicha con la serenidad de alguien que ha pasado décadas clasificando, contando, diseccionando y transformando materia como quien relee su propia vida— resume mejor que nada el espíritu de La Petite Mort.

La exposición no solo recorre dos décadas de obra, sino que permite ver por primera vez el hilo subterráneo que la une: una pulsión obsesiva por revelar lo que queda cuando algo se desgasta, se quema, se corta o se pierde; su obsesión con la transformación y la paciencia que caracteriza su obra. Bajo la curaduría de Tobias Ostrander, el recorrido avanza como un tránsito por distintos estados del deseo y la desaparición: del cuerpo que se ofrece como superficie, de la piel que archiva memoria, del material que muere para transformarse en otra cosa.

En estas salas, Gabriel de la Mora confirma algo que en su estudio parece casi ley física: “el arte no se crea ni se destruye, solo se transforma”. Y al cambiar, expone también al artista. Porque mirar de cerca estas piezas —a veces tan minuciosas que obligan al cuerpo a acercarse casi hasta contener la respiración— es mirar la compulsión, la paciencia, la levitación mental y el archivo íntimo que sostienen su obra.

La Petite Mort es una exposición sobre la pérdida, sí. Pero también sobre la manera en que esa pérdida se vuelve conocimiento, placer estético y, sobre todo, continuidad: un puente insospechado entre un dibujo hecho por un niño de cuatro años y un artista que, más de treinta años después, sigue buscando que su obra se mantenga en el aire… sin tocar el piso.

¿Qué tipo de “pérdida” buscas provocar en el espectador con tu obra?

Siempre que algo se pierde, algo se gana. Al perder materia, por ejemplo, se revela nueva información: un desgaste, una acción, un tiempo. La pérdida se convierte así en otra forma de conocimiento.

Me refiero quizá a que en este mundo todo lo que existe está aquí para cumplir una función o un servicio, cuando esto termina, el fin de algo puede transformarse en el inicio de algo más.

Mi definición de arte es un paralelo a la definición de energía: El arte ni se crea ni se destruye, tan sólo se transforma.

El título insinúa placer y extinción al mismo tiempo. ¿Hay un punto donde el deseo y la muerte se vuelven indistinguibles para ti dentro del proceso artístico?

El título de la exposición lo puso el curador Tobias Ostrander, La muerte pequeña o pequeña muerte. Citando un artículo que escribió Susan Crowley en torno a esta exposición comparte lo siguiente: “Para George Bataille la petite mort no se refiere al acto físico de morir, es la metáfora de la experiencia al límite donde la conciencia es suspendida momentáneamente por un placer intenso.”

Tobias de alguna forma apunta hacia el placer físico y estético.

La muerte marca un final de algo, que a la vez marca el inicio de algo más a través de la transformación.

Tus procesos están llenos de clasificación, disección, conteo, acumulación. ¿Qué parte de tu psique se activa cuando entras en esa meticulosidad extrema?

No sé si “obsesión” o “repetición” podrían ser una respuesta a esta pregunta, pero el proceso es algo muy importante para mí en todo. La clasificación y el archivo son otra parte esencial de mi trabajo: todo lo que ocurre antes o durante el paso de una idea a una pieza o a una obra es algo que generalmente el público no ve, y a mí me gusta documentarlo de diversas maneras; estas anotaciones y registros forman parte del archivo de cada pieza o serie.

La repetición, en realidad, no existe: nunca habrá dos cosas idénticas, porque en cada intento siempre surgen diferencias. Como dice Gilles Deleuze en su libro Diferencia y Repetición (1968), que curiosamente es también mi año de nacimiento, cada repetición es, en sí misma, una variación.

Noté que algo que caracteriza tu obra es la paciencia, la cual parece operar casi como un estado mental paralelo ¿Qué has descubierto sobre ti mismo en esos procesos de tu obra que solo existen en la lentitud?

La paciencia es uno de tantos elementos clave en mi trabajo, y se hace evidente todo esto al colocar cientos o miles de fragmentos de cascarón de huevo sobre un panel de madera, contando cada fragmento pegado. Al final, la cantidad total de fragmentos en la superficie será el título de la obra un número que solo se conoce al concluirla.

El realizar un trabajo en donde además de la concentración, es una acción repetida, llevándote a un estado cercano a la meditación, y justo es donde aparecen una gran cantidad de ideas, las cuales se van apuntando y esperan el momento para poder ser exploradas y ejecutadas.

Trabajar en el estudio se asemeja a meditar, y todo esto lleva a lo que comentas en la pregunta, a la levitación o a la lentitud entre muchos elementos o factores más.

El silencio, activado por el click de cada contador al pegar cada fragmento genera un estado muy especial: una nota continua al infinito, un estado en el que cualquier color desaparece quedando un blanco absoluto rodeado de ideas, no sé si el tiempo se detiene o desaparece, no sé si en este estado se respira y esto hace realidad de alguna forma uno de tantos sueños que he tenido desde niño: es volar y caminar sin tocar el suelo, lento y frio.

¿Qué te atrae de materiales que otros considerarían desecho? ¿Te interesa su historia, su carga energética o su condición de residuo?

El desecho es algo que ha cumplido su función original y está a punto de ir a la basura o desaparecer. Todos estos materiales contienen información sobre la acción o el propósito que tuvieron; llevan una energía propia. A través de distintos procesos, y con el apoyo y asesoría de restauradores, hago que ese deterioro se detenga: se consolidan para extender la vida de estos materiales transformados en arte, preservándolos el mayor tiempo posible y en las mejores condiciones.

Busco responder todas las preguntas que me surgen en cada material que me atrae y comienzo a recolectar. También me interesa que una idea pueda dejar una obra, que un conjunto de obras genere una serie y, a veces, incluso una nueva técnica. Cuando eso sucede, para mí surgen las series o piezas perfectas. Me encanta emocionarme con ciertas ideas, pero disfruto aún más cuando los resultados superan cualquier expectativa y terminan siendo mucho más de lo que podría imaginar o esperar.

Dices que el artista no crea ni destruye, sino transforma. ¿Qué te hizo desprenderte de la idea romántica del artista como “creador”?

Lo mismo que me ha llevado a cuestionarlo todo en torno a la autoría, al final lo único que importa y lo único que siempre existirá será la obra de arte que irá cambiando constantemente hasta que desaparezca; y cuando esto suceda se transformará en algo más.

Por eso aseguro que en la pirámide del arte solo existen 4 letras: las de ARTE o de OBRA, ya que todo lo demás incluyendo al autor desaparecerá. Por eso el Museo de Antropología de la Ciudad de México es mi museo favorito al que trato de ir constantemente, ahí no existe ningún nombre, ningún autor, las tallas en madera o piedra perdieron su color, sus policromías, y sin embargo siguen siendo obras maestras, en ocasiones siguen siendo vanguardia.

¿Cómo dialoga tu obra con la idea de piel: como frontera, como archivo o como superficie de deseo?

La piel es un tema que siempre me ha interesado, y quizá por eso llegué a la serie de pinturas en la que mezclo mi sangre con barniz en capas sucesivas hasta alcanzar el tono de mi piel, aplicando luego diversos cortes con una navaja. De alguna manera, esto genera autorretratos y conecta con los inicios de la pintura, evocando incluso las pinturas rupestres.

Me atrae la idea de la piel como frontera, como archivo y también como superficie del deseo: la línea que divide el interior del exterior, la vida de la muerte.

Algunas piezas requieren una proximidad casi íntima para ser vistas. ¿Qué significa para ti acercar el cuerpo del espectador a una escala microscópica?

Me fascina la idea de que el espectador se acerque, pero sin tocar la obra. Cuando esto sucede, las piezas se activan, y de alguna manera la energía de quienes las miran es absorbida por los materiales y la obra misma. Todo esto se guarda como información, y el público, de algún modo, se convierte en parte de la pieza.

Si la muerte está latente en tus procesos, ¿qué significa para ti hacer obras que terminan entrando a colecciones y museos, donde se “conservan”?

Al inicio de mi carrera me quedaba con todo lo que hacía; me gustaba controlar y conservar cada pieza en su mejor estado. Me costaba mucho trabajo soltar, regalar, vender o dejar ir obras, porque me daba miedo que se dañaran o incluso que se perdieran.

Con el tiempo aprendí a soltar y dejar ir, porque también me emociona que a alguien le guste una pieza o mi trabajo y quiera tenerla, comprarla y, gracias a eso, permitirme vivir de lo que más amo: ser artista y hacer arte.

Cada obra que sale del estudio tiene que doler un poco. A veces, cuando una pieza no se vende y regresa a mí, me encanta volver a verla y tenerla como parte de mi colección. La única razón por la que permitiría que una obra saliera de mi colección es que un museo estuviera interesado en tener algo de esa serie. Esa es una de las pocas formas en que una pieza dejaría de ser mía: para integrarse a una colección institucional, exhibirse y activarse a través del público. Además, los cuidados de un museo son extremos, y eso permite que las obras permanezcan el mayor tiempo posible en las mejores condiciones.

¿Qué papel juega la compulsión en tu manera de trabajar? ¿Es motor, método o consecuencia?

Todo y nada a la vez. La compulsión, la obsesión, los comportamientos repetitivos, la pasión y la intensidad son algunas de las muchas características que me definen.

Como diría Billy Elliot al intentar describir lo que para él es el baile: electricidad. La electricidad también es una palabra que podría responder esta pregunta: es motor, método, pulsión y consecuencia.

Paso casi todo mi tiempo en el estudio. Solo termino el día porque tengo que comer, dormir y descansar; de lo contrario, estaría trabajando y pensando 24/7. A veces resuelvo piezas o problemas en sueños; por eso siempre tengo una libreta y un lápiz en el buró. En ocasiones me levanto de madrugada para anotar una idea o resolver algo. Incluso cuando camino o manejo, sigo trabajando mentalmente, pensando, imaginando piezas y series.

Generalmente solo realizo quizá el 3% de todo lo que escribo. La inspiración surge del trabajo mismo y de las ideas, y ese círculo continuo es la forma en la que vivo, pienso y trabajo, esté en el estudio o en mi casa.

Después de 20 años de trabajo reunidos en una sola exposición, ¿qué te sorprendió más de reencontrarte contigo mismo?

Las 87 piezas de la exposición corresponden a 22 años de mi carrera, dentro de un periodo total de 30 años (1996–2026). Muchas de las obras que integran La Petite Mort se exponen por primera vez.

Algo que me ha sorprendido mucho es que varios coleccionistas, críticos, curadores y amigos —personas que han seguido mi trabajo durante años— me han dicho que creían conocerlo, y que al ver la exposición se dieron cuenta de que no lo conocían realmente. Se emocionan y se sorprenden, y escuchar eso me hace reflexionar profundamente.

Yo mismo veo cada exposición como si fuera la primera; me emociona que lo que más disfruto de mi trabajo sea lo que estoy haciendo ahora y lo que viene. Por supuesto, siempre habrá piezas clave en el camino, pero ojalá nunca llegue el día en que lo mejor de mi obra esté 10 o 20 años atrás. Si eso sucediera, tendría que replantearlo todo… o quizá pensar en jubilarme, aunque siempre he creído que un artista no se jubila: la jubilación del artista es la muerte.

Algo que me impactó enormemente fue descubrir que la primera obra que hice, a los cuatro años en 1972, está conectada con todo mi trabajo de estos primeros 30 años de carrera.

Y hubo una pieza que me sacudió de manera especial: Memoria I, el retrato familiar hecho con cráneos, de la serie Brújula de Cuestiones (2007). Tenía más de diez años sin verla. Durante el montaje, los soportes y los 17 cráneos estaban en el piso, listos para instalarse. Verlos ahí me golpeó profundamente.

David estaba grabando el proceso, y junto a él estaban Kit Hammonds, curador del Museo Jumex, y Tobias Ostrander, curador de la exposición. Sentí que las lágrimas estaban por salirme; dejé de respirar por un instante y retrocedí muy despacio. David dejó de grabar, y de pronto hubo un silencio absoluto. Al hacerme hacia atrás y mirar a Kit y a Tobias, que estaban serios y mirando al piso, exploté.

Me impresionó que la obra mostraba los cráneos en vida de mi abuela y de mi madre, quienes ya no están, y eso me provocó una emoción extrema. De alguna forma, esa pieza activó el inicio del montaje de la exposición, un proyecto que en un principio yo mismo no entendía, pero que, al verlo terminado, puedo decir que es la mejor exposición que he presentado hasta ahora.

Aun así, cada exposición en museo o galería que he hecho ha sido impecable e importante. Y espero que las que vengan sean siempre mejores que las anteriores, igual que mi trabajo y todo lo que hago. Deseo nunca dejar de emocionarme y sorprenderme, y seguir siempre feliz… sin tocar el piso.